Irving Penn: Centennial at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

April 24th– July 30th, 2017

By Elizabeth Aaron

To me personally, photography is a way to overcome mortality.

Marking the centennial of Irving Penn’s birth, the Metropolitan Museum of Art presents 187 of the celebrated photographer’s finest works from the Irving Penn Foundation. Though primarily celebrated as one of the most influential fashion photographers at Vogue, this major retrospective is an exquisite documentation of his expansive history as an artist. As often ahead of his time as he was lauded within it, it covers every facet of his 70-year career in 10 catalogues from his major series.

A master of photography in its final analogue form, Penn was an image maker in the old style, largely eschewing color photography for black and white prints and teaching himself the laborious, unfashionable platinum and palladium printing in the 1960s. He believed in the camera and the dark room, the camera and the hand, studying the art of Goya, Daumier and Toulouse-Lautrec to enhance his own lighting, focus and reductionist graphic composition. As Jeff L. Rosenheim says, there is a “distilled genius in all those pictures.”

The daylight… is the light of Paris, the light of painters. It seems to fall as a caress.

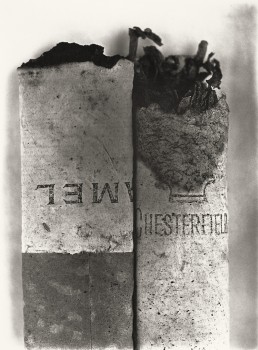

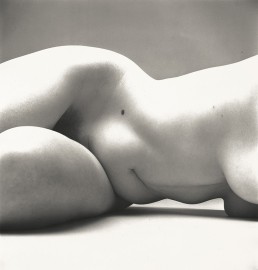

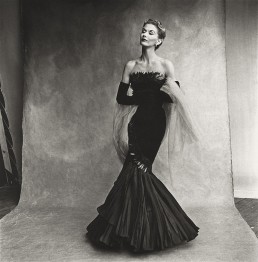

Penn’s favored backdrop was an old Parisian theatre curtain painted with diffuse soft grey clouds that followed him from studio to studio over a period of 60 years. The classic Vogue photographs of sublime Dior and Balenciaga couture worn by, amongst others, Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn, display his incomparable fashion nous. Yet it is Penn’s unquenchable thirst for experimentation, such as his bleached and overexposed nudes of “real women in real circumstances”, that give the delighted viewer a sliver of insight into the curiosity of his mind. The Nudes were ill-received in the 1950s, as were his later still life portraits of crushed cigarette butts and decaying flowers. “Why make achingly beautiful prints of something beneath regard?” The fragility and minimalism of that which has “passed that point of perfection”, is testament to Penn’s utter modernity; that which makes an artist iconic.

I myself have always stood in awe of the camera. I recognize it for the instrument

that it is, part Stradivarius, part scalpel.

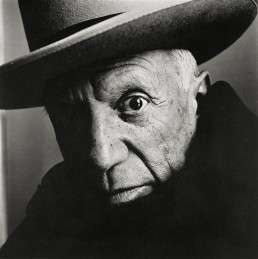

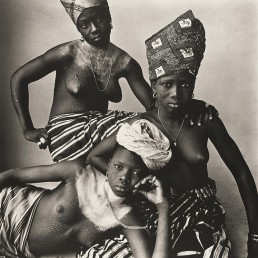

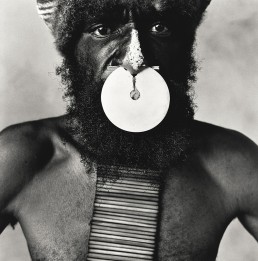

Curator Maria Morris Hambourg beautifully describes The Photographer as often being either the hunter, surreptitiously snapping as did Cartier-Bresson, or a magnificent studio stylist in the manner of Richard Avedon. Irving Penn was “something of a hunter seeking something deeper than the surface, longer than a moment.” Photographing celebrated artists from Colette to Capote and Picasso, to the beautiful indigenous peoples of Benin, New Guinea and Morocco, one senses this deep respect for the idiosyncrasies of each sitter. It is this deft unravelling of a part of the soul beyond the shroud of textile that gives a profound feeling of emotion to Penn’s work, in addition to the delicacy and finesse of his portraits.

Irving Penn: Centennial will be travelling to Paris, Berlin and Brazil.