Personally, I don’t care about function at all. …When I hear ‘where could you wear that?’ or ‘it’s not very wearable,’ or ‘who would wear that?’ to me it’s just a sign that someone missed the point.

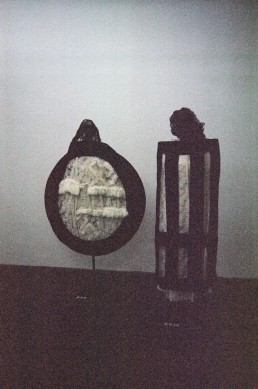

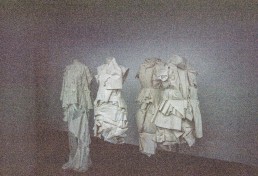

In the first major retrospective for a living fashion designer since Yves Saint Laurent, the Metropolitan Museum of Art honors rule-transcending Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons in “Art of the In-Between”. A designer-disruptor, her enigmatic and unconventional aesthetic is curated into nine themes: Absence/Presence, Design/Not Design, Fashion/Antifashion, Model/Multiple, High/Low, Then/Now, Self/Other, Object/Subject, and Clothes/Not Clothes. Magnificent even when she intends to be monstrous, Kawakubo’s searing dedication to creative autonomy is ever grounded in a delicacy of workmanship that at times feels like a pilgrimage.

If we say ‘these are clothes,’ it’s all very usual, so we said ‘these are not clothes.’ It sounds like a Zen dialogue, but it is very simple.

Kawakubo’s collections explore the nature of Zen koans, in the interaction between mu (emptiness) and ma (space), investigating the inherently paradoxical dichotomies of beauty and ugliness, truth and artifice, body and void. In her collections, she is seeking Gesamtkunstwerk or the “total work of art”, considering herself to be a worker rather than an artist. The germ of each storytelling arc might be an abstract image or even a single word; she once gave her pattern designers a crumpled piece of paper. It is this “design without design” and dedication to “newness” that encapsulates the Zen principle of wabi-sabi. Kawakubo has harkened back to this in two ruptures during her creative career; the first in 1979, when she “decided to start from zero, from nothing, to do things that had not been done before,” and more recently in 2014, with her radical aspiration to create transgressive “objects for the body… forms that have never before existed in fashion.”

I wished there was a new psychedelic drug that allowed me to see the world differently, through the eyes of an outsider.

It is this morphological eccentricity and ideological severity that has historically baffled some critics, who have not understood her unsettling “ugly aesthetic.” Yet beyond the architectural splendor of her silhouettes and the richness of craft in her textiles, there is a pervading sense of surrealistic play throughout the exposition. Even when Kawakubo tackles dark subjects, her clothing rendering the body malformed and engorged, she is expressing “the absence of ordinariness… by something that could be ugly or beautiful.” It is this upending and subversion of aesthetic canons, a symbolic defiance of tradition in pursuit of pure form, that captures a soulful and uncompromising hybrid identity both of and beyond culture, gender, beauty, and age.

Words and Photography by Elizabeth Aaron